Brigham and Women’s Hospital is ranked #1 in the nation for Obstetrics and Gynecology by U.S. News & World Report…

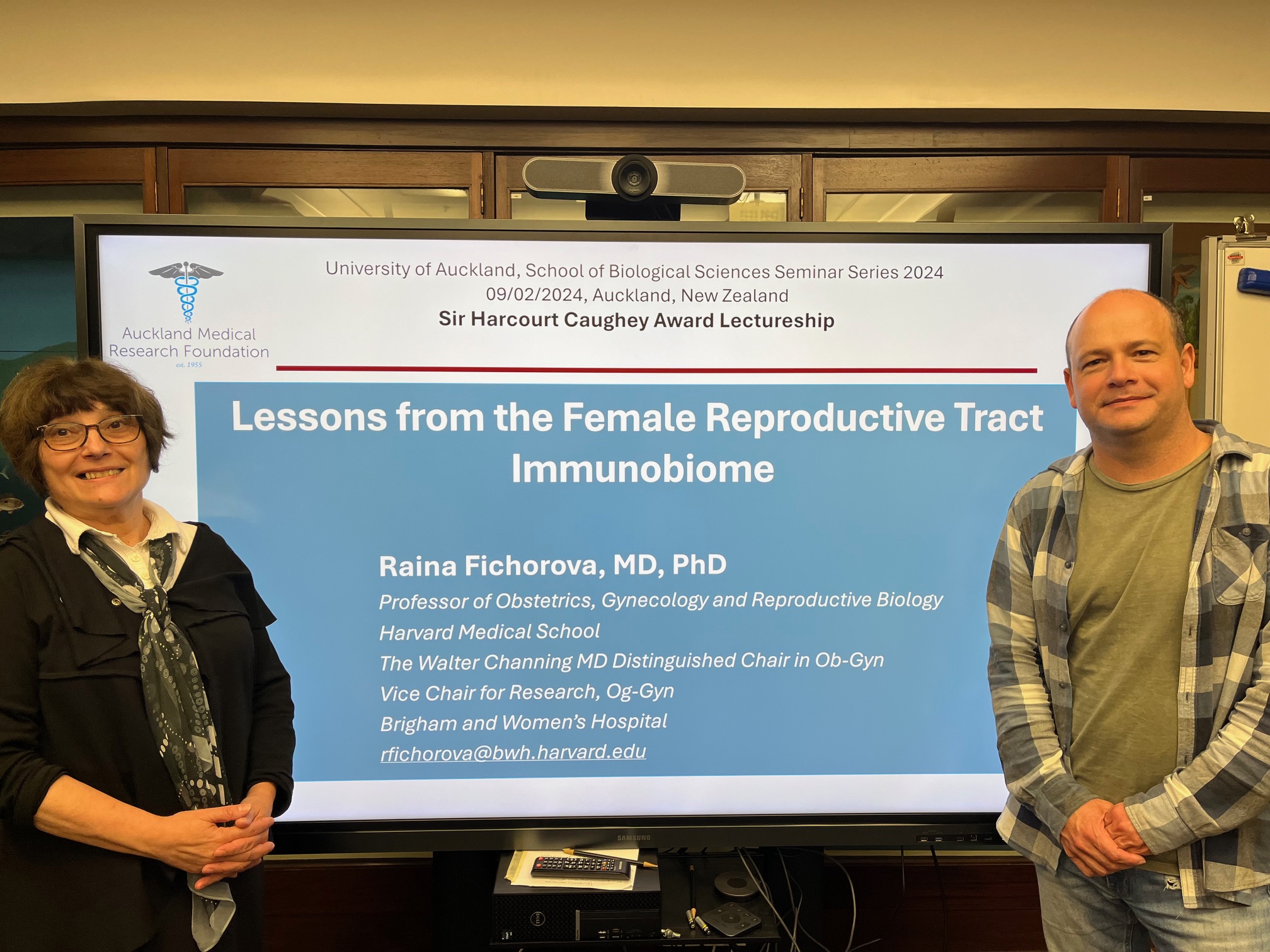

Raina Fichorova, MD, PhD: Innovative Reproductive Immunologist Envisioning a Healthier Generation

Raina Fichorova, MD, PhD: Innovative Reproductive Immunologist

The Boston Lying-In laid the foundation of the Brigham as the first hospital in New England to provide a safe birthing place for women in 1832.

Raina Fichorova

June sunlight washes over the beige exterior of 221 Longwood Ave as visitors, faculty and staff enter and exit the Brigham building. But amidst the daily hustle and bustle, Raina Fichorova, MD, PhD, takes a moment to turn her gaze upward to the intricate carvings of storks and swaddled babies dotting the building’s façade.

“This was the first birthing hospital of its kind in New England — before it opened its doors, women delivered babies in their kitchens and poor women had no place to obtain midwifery care,” said Fichorova, the Walter Channing MD Distinguished Chair in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Brigham and a Harvard professor.

It wasn’t until Walter Channing co-founded the Boston Lying-In Hospital in 1832 that women had a place to give birth safely. It was specifically dedicated to the care and relief of poor and deserving women. Channing’s legacy is at the root of Fichorova’s desire to provide all women with equal opportunities to have healthy pregnancies and babies. “I am so happy and so proud to work here,” she said, adding that she’s been with the Brigham for more than 24 years.

As a reproductive immunologist, her current research focuses on how microbes in the female genital tract influence innate immunity and inflammation. Understanding these microbial mechanisms will inform the creation of new therapies to improve reproductive health and prevent HIV and cancer.

Fichorova was born into a family of physicians in Bulgaria. Her hometown of Pazardjik is situated at the geographic crossroads of the East and the West, she explains. Exposure to multiple cultures and religions co-existing in peace and respect nurtured her passion for seeking health equity across ethnic, religious and socioeconomic lines. She obtained her MD and PhD from the Medical University of Sofia, then completed a fellowship in reproductive immunology at the Brigham.

This year, Fichorova received a $4 million, five-year R01 grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study non-coding RNAs. According to her hypothesis, these molecules are influenced by the mucosal environment of the female reproductive tract, and control genes predictive of HIV susceptibility and systemic inflammation. A clearer understanding of these RNAs and genes will aid in the development of novel therapies and disease prevention strategies.

Fichorova’s team inspires and nurtures the next generation of women scientists and innovators in medicine.

Envisioning a Healthier Generation

Fichorova is also participating in a seven-year, nationwide NIH initiative called Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO), which explores how an array of environmental factors affect early development in over 50,000 children from diverse backgrounds. Fichorova’s lab is studying inflammation in mother-infant pairs in which the ECHO team is measuring environmental contaminants, nutritional factors, neurodevelopment and other child health outcomes in the context of the greater social and psychological environment.

“We have to break disparities in women’s health by understanding environmental factors that are modifiable,” Fichorova said. “These include the microbes that we acquire through birth and through environmental interaction.”

Fichorova thrives at the Brigham, which provides her with a friendly, stimulating environment that helps fuel her numerous innovations. She has developed special immortal lines of epithelial cells originating from healthy uterine and vaginal tissues that are easily used to study infection, immunity and cancer. Scientists around the world now use these cells to physiologically model the human reproductive tract.

Now, she’s hard at work on a new biotherapy: a cocktail of bacteria selected by a complex algorithm. This new therapy will have multiple applications for women who are trying to become pregnant and to treat dysbiotic conditions and inflammation in women of all ages.

Fichorova’s research on inflammation and the microbiome will not only promote mothers’ health; it will also bolster the wellbeing of their children.

“Inflammation at the time of birth plays a role in a child’s future potential,” she said. “If we can understand what’s happening, it would be a gold mine. We could have a healthier generation.”